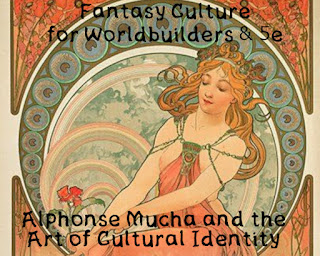

Alphonse Mucha and the Art of Cultural Identity

by Ty Hulse

The 19th and early 20th Century was defined by the idea of nationalism, or more specifically the search for a common identity with other people's who spoke the same language or had similar histories. Romantacism as an art exalted passion and emotions above enlightenment values of logic and the social good. The romantic artists loved fairies and magic, primarily as it was associated with folklore. The Brothers Grimm were inspired to collect German tales and lore based on this idea, in hopes of unifying the many German nations into a single whole. They were frequently in conflict with kings and nobles

Certainly, Alphonse Mucha, famous in Paris for helping create the Art Nouveau would join a movement of artists and idealists seeking to bring independence to his Slavic Czech homeland. He believed that art inspired by the fantasies, myths, and folklore of the Slavic people could help inspire a revolution. He was inspired to this end while in Paris, as he said;

“It was midnight, and there I was all alone in my studio… I saw my work adorning the salons of the highest society or flattering people of the great world with smiling and ennobled portraits. I saw the books full of legendary scenes, floral garlands and drawings glorifying the beauty and tenderness of women. This was what my time, my precious time, was being spent on, when my nation was left to quench its thirst on ditch water. And in my spirit I saw myself sinfully misappropriating what belonged to my people. It was midnight and, as I stood there looking at all these things, I swore a solemn promise that the remainder of my life would be filled exclusively with work for the nation.”

After this he left Paris, returning to his Czech homeland in order to create art that would inspire his people, including a series of fantastical paintings inspired by Pan-Slavic writings. Pan Slavism was a cultural movement that stated in the middle of the 19th century. While his art was revolutionary and a call to overthrow the Austrian government, Mucha could discuss them in terms of fairytales to avoid the ire of the authorities.

The public was lacking something. It was obvious that it needed to breathe fresh air and find peace and harmony. The existing harmonies were exhausted, empty, taken over from old Renaissance motives, and people were glad to quench their thirst for beauty with a new draught. It seems that it was the refreshing new Slav element they were looking for. Posters were a good way of educating a whole population. They would stop on their way to work and derive from them spiritual pleasure. The streets became open-air art exhibitions.

The goal of these movements was largely positive, to escape the repression of dictators. In order to achieve these ends people created a falsified history and mythology. For example, they sought to portray the Slavs as peace loving, as having been over taken by the violent warrior Germanic people. This, of course, ignores the fact that the Slavs were only in Western and Central Europe because they had fought to displace the people who were already there. In order to create their new cultural identities, many people invented many of the fantasy elements and even the myths we still cling to today. The idea of a preexisting earth mother being one such myth.

Obviously the people who were being oppressed at the time deserved the right to escape repression, what’s interesting for us is that the fantasies people created were able to trump reality, because fantasy and lore are powerful forces.

Mucha described his posters in the following terms:

I must choose a technique which doesn’t take too long. . . .This is why I think oil painting is too technical and not suitable for expressing ideas. In oils the technique is always visible, and this I don’t want . . . if it is broadly painted it’s just shallow virtuosity, unworthy of serious subjects. And if it is too meticulous and naturalistic, the harsh colours will kill the idea and the whole thing looks terribly heavy handed and forced. My work must be like sudden shouts without any bravado technique, honestly felt and honestly expressed, with no showing off, no acrobatics of the brush. I think I will do it like the tragedy of the German Theatre, only better and more seriously worked out, with the main stress on drawing, while the colour, harmonious and natural, should be subordinate. Now I’m looking for a method and I think I have found it. Contemporary oil technique has nothing in common with the Slav spirit. . . it is French, or Dutch, perhaps even German or Italian, but not Slavonic. We must start from a completely different angle . . . not painting because … we get satisfaction from effects of light and colour, but because . . . painting is a more direct way of conveying feelings. And these feelings must remain the principal object while technique and colour must be subordinate. This is my new approach . . . and perhaps I’ll be able to do something really good, not for the art critics but for the improvement of our Slav souls.”

Epic Significance: Placing Alphonse Mucha's Czech Art in the Context of Pan-Slavism and Czech Nationalism Erin M. Dusza (2012)

“Mucha’s advertising posters reflected a new mythology of modernity: the desire for universal harmony and happiness.”

The Image of Homeland in the Works by Alphonse Mucha “Madonna of the Lilies”, the Poster for “The Lottery of the Union of Southwest Moravia” and the Poster for “The Slav Epic Exhibition” Yuliya S. Zamaraeva*, Kseniya V. Reznikova and Natalya N. Seredkina 2020

0 comments:

Post a Comment